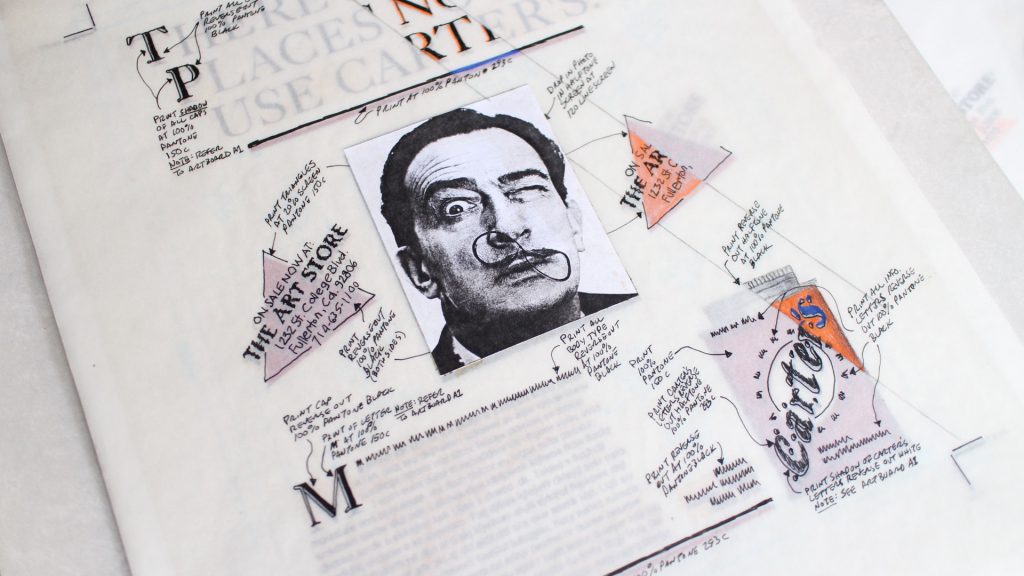

After I graduated from college in 1993, I got an internship at an annual report firm. We were designing and producing spreads, by hand, onto boards. Our process included thumbnails, sketching, drawing a grid onto the board, ordering type over the phone, trimming out type galleys, hand-kerning type, waxing it down, and so on. You could say it was a lot of work and it took a long time.

This process was great, because you became intimate with the projects because you had your hands on them. You had to know your tools and type really well. Our office was not yet using computer software for design and production, so the task ended up on me to make the transition.

This process was great, because you became intimate with the projects because you had your hands on them. You had to know your tools and type really well. Our office was not yet using computer software for design and production, so the task ended up on me to make the transition.

My boss taught me the fundamentals of the grid and typography well, but it was really up to me to figure out how to translate those skills to the computer. (I talk about my experience in this video.)

Remember, there was no YouTube at the time. There was no Google. If you wanted to learn software, you had to take classes in-person. So I learned Quark XPress 3.1 and Illustrator 88 in the Art Center at Night program.

There was a lot to figure out because I was trying to connect the abilities of the software to solving the actual problems I was facing during the day. I was taking what I learned in class and trying to figure out how to translate those tools for application at work.

And through this process I learned two lessons, which eventually influenced my teaching style today:

- It’s important to understand the fundamentals and how to apply them in the software. Tool training is, and should be, integrated into the learning process. I’ve taken classes where I was presented a problem with a goal in mind, but expected to figure out how to do it with little guidance. To often, educators don’t want to teach software, only theory. But teachers need to help with application and tool training. Sure, software tutorials can be found online and students need to be resourceful; but applying and handling type is a craft, much like playing music. For example, music teachers do not just hand over a sheet of music, share a recording of the song, and then expect a student to recreate it. Once the tool is learned, constant practice is needed. It takes finesse and feeling to make type sing.

- The mindset of design is very important. In my perpetual learning of design (and yes, to this day I’m still learning), it’s crucial to know the WHY, as well as the HOW. If one doesn’t understand why parts of the process is essential to the whole, then one won’t understand how to prioritize when things change. The mindset helps to apply, add new and change processes while maintaining integrity when there shifts in the field.

In my 22-year design career, I’ve seen typesetting houses come and go, photographers struggle in the popularity of stock photos, and print shops shift from to digital just to stay in the game. Be assured that there will be more shifts coming in the field of design. This is why I think we need to keep adjusting and updating our skills so we can handle whatever design challenge comes along.

What won’t change is how people naturally read and the psychology of how design communicates. Humans are visual. And that’s why the fundamentals are important.

How have you shifted your process over time? Please let me know by tweeting us @TypeEd. I’d like to hear where you came from and where you’re going. And if you know anyone who might be inspired by this, feel free to share!

Michael Stinson is a co-founder and lead instructor at TypeEd, where he helps designers implement better typography, efficiently. Learn more about how to design for readers by signing up for TypeEd courses.