We are in an age of breakneck progress in artificial intelligence — the chatbots have given way to AI tools that can create impressive, highly detailed images. Is it time to worry or rejoice?

Say hello to an emerging and fast-evolving genre of AI known as text-to-image generation.

It’s a fascinating new front in artificial intelligence, where anyone can generate hyper-realistic images from a written text description.

While most users have generated work that leans toward the weird and absurd, like the Mona Lisa painting a portrait of Da Vinci, many are also experimenting with possible commercial applications. As you might imagine, this tech has stirred up deep existential and ethical questions about art, creating, and more. Who is the artist behind the creations — AI or its human user? Can machines be creative? And perhaps most germane for creatives — Will this new technology make certain creative industry jobs go *poof*?

Just this past midsummer 2022, a select few people in and adjacent to the tech industry were granted access to these text-to-image AI tools during initial beta testing. The two most prominent are Dall-E —derived from the name of the surrealist artist Salvador Dali and Pixar’s lovable animated robot Wall-E —and Midjourney. Dall-E was launched last year by OpenAI, a nonprofit research lab founded by Sam Altman, Peter Thiel, and Elon Musk, among others. Midjourney entered open beta in mid-July 2022 and comes from a self-funded AI research lab founded by David Holz.

These AI text-to-image tools are simple to use — but rife with controversy.

You can open the doors to a dazzling cornucopia of visual creation in seconds with just a few words or simple phrases. Here’s how these AI tools work: Users type in a text prompt like “a frog on a united states quarter” or “chickens gathered to watch human wrestling,” for example, and the results are wild. These programs can translate text into award-winning art that has roiled the art and design community.

The New York Times recently published an article, “An A.I.-Generated Picture Won an Art Prize. Artists Aren’t Happy,” chronicling the brouhaha around the Colorado State Fair’s annual art competition awarding Jason M. Allen, of Pueblo West, CO, with the blue-ribbon prize in Digital Art for a piece he had created with Midjourney (he won $300).

via Jason Allen

Allen’s work, “Théâtre D’opéra Spatial,” won the fair’s contest for emerging digital artists, making it one of the first AI-generated pieces to win such a prize, provoking fierce criticism from artists who accused him of “cheating.” Allen defended his work, which in submission he had explicitly labeled “Jason M. Allen via Midjourney.” After winning, Allen posted a photo of his prize piece to the Midjourney Discord chat, which made its way to Twitter, where it ignited heated debate and backlash. Here are some excerpts from the online mêlée.

- “This is so gross. I can see how AI art can be beneficial, but claiming you’re an artist by generating one? Absolutely not,” shared one Twitter user.

- “We’re watching the death of artistry unfold right before our eyes,” another Twitter user wrote, who was quoted in the New York Times piece.

- “No effort? Please,” another wrote. “If Jackson Pollock can splatter paint onto a canvas or Maurizio Cattelan can tape a banana to a wall, and both are called “art” (both which take hardly “any effort at all”), then this counts too.”

- “Fine tuning and curating is the art here. If they just presented generic Midjourney art, then… It wouldn’t have won. Figuring out what looks like good digital art is the art itself.”

Some tweets excoriated Allen, while others defended him. Many argued that using AI is no different from using other digital image manipulation tools like Photoshop, and that human creativity was necessary to craft the right prompts and curate the final award-winning piece.

Controversy over new art-making technologies is nothing new.

The New York Times article shared that “controversy over new art-making technologies is nothing new. Many painters recoiled at the invention of the camera, which they saw as a debasement of human artistry. (Charles Baudelaire, the 19th-century French poet and art critic, called photography “art’s most mortal enemy.”).”

Is text-to-image AI different? Maybe, maybe not. Regardless, human artists are, however, understandably anxious about their futures. Will anyone pay for art or design if they can just generate it themselves? Or are these just new tools that will augment concepting and prototyping, freeing artists, designers, marketers, and more to focus on the more directional components of creation?

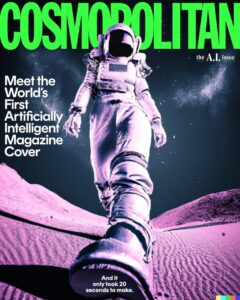

Just this past June, Cosmopolitan commissioned art director and digital artist Karen X Cheng to produce the magazine’s first-ever AI-generated cover art — a strong woman shown as an astronaut, based on creative direction from Cheng and the Cosmo design team. The headline and lede on the cover read, “Meet the world’s first artificially intelligent magazine cover. And it only took 20 seconds to make.” While it took Dall-E twenty seconds to render the image, that bombastic but attention-grabbing claim does not take into account the time it took to refine the art direction or compose the right prompt to achieve the final image.

Cheng documented the process and posted the video on Instagram, which showed the hundreds of iterations of text prompts she typed before coming up with: “wide-angle shot from below of a female astronaut with an athletic feminine body walking with swagger toward camera on Mars in an infinite universe, synthwave digital art.”

Via Cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan wasn’t the only magazine with an AI-produced cover this past June. The normally buttoned-up Economist deployed a Midjourney-created piece emblazoned with the headline: “AI’s New Frontier.” These examples are significant because they show how quickly digital technologies can go from bleeding edge to market, giving rise to a panoply of complex emotions.

What is the future of text-to-image AI, and what does it mean for artists and designers?

Advances in AI have often sparked concern about the displacement of human workers. While those concerns are legitimate, IBM CEO Ginny Rometty recently said, “If I considered the initials AI, I would have preferred augmented intelligence.”

One way to look at this new technology is that it can help push creative visions forward. Someone putting together a presentation might find they can communicate ideas visually that surpass their artistic abilities. The production team for a video shoot can quickly test out backdrops and props ahead of time. An advertising agency can tweak drafts of a new campaign before having artists work on the final concept.

The reality is that AI design tools are already a part of the creative industry. The Adobe Creative Suite is full of AI-enhanced features. Premiere Pro has proprietary Adobe Sensei AI embedded, allowing automated captions to be created. In Illustrator, the ability to trace and vectorize sketches is powered by AI, as well as the skin-smoothing and other retouching tools in Photoshop’s neural filters.

This compendium of AI use cases from the last several years shows how ubiquitous automated design has become, but it also demonstrates that without creative intervention from human artists and designers, the results of AI-generated design can feel derivative, regimented, and homogenized — making the case that without a human to steer the way, this technology has no intrinsic soul. Perhaps the future is for humans to be captains of creation, with a growing array of digital tools at their disposal.

About the author.

An award-winning creator and digital health, wellness, and lifestyle content strategist—Karina writes, produces, and edits compelling content across multiple platforms—including articles, video, interactive tools, and documentary film. Her work has been featured on MSN Lifestyle, Apartment Therapy, Goop, Psycom, Yahoo News, Pregnancy & Newborn, Eat This Not That, thirdAGE, and Remedy Health Media digital properties and has spanned insight pieces on psychedelic toad medicine to forecasting the future of work to why sustainability needs to become more sustainable.