Hand lettering is huge these days, and is inspiring many designers to add hand-lettering to their skill sets. With the explosion of the sharing economy, designers are learning from each other.

Hand-letterers craft letters using mark-making tools for a specific application or use. What’s the best way to get started or level up in lettering? These six up and coming hand-lettering artists use their skill to create artwork that evokes meaning and expression. Get their best advice on how to improve your own skills.

The Details Matter

Joseph Alessio is a typographic illustrator based in San Francisco who blends type, letters and animates a host of mixed media in typographic compositions. Joseph’s approach with spatial relationships in type and motion is unique. He loves that part of the process in the middle, when you feel like you can experiment and play and discover – “that’s to me the most exciting and fulfilling part.”

Joseph Alessio is a typographic illustrator based in San Francisco who blends type, letters and animates a host of mixed media in typographic compositions. Joseph’s approach with spatial relationships in type and motion is unique. He loves that part of the process in the middle, when you feel like you can experiment and play and discover – “that’s to me the most exciting and fulfilling part.”

-

-

Joseph recommends any of Doyald Young’s books as resources for new letterers. “He has an impeccable sense of composition and spatial relationships, how to handle flourishes, etc, and you can learn so much by studying his sketches.” He also recommends for understanding the nuance of letterforms is Designing Type by Karen Cheng. “It’s ironically not about actually designing type, but rather examines in great detail the minutiae of stroke weights, optical adjustments and balancing, character dimensions etc., and was really eye-opening for me as to how quality letterforms, especially within the context of working with other letterforms, are crafted.”

Find Joseph on Instagram, Twitter or his website.

The Fundamentals

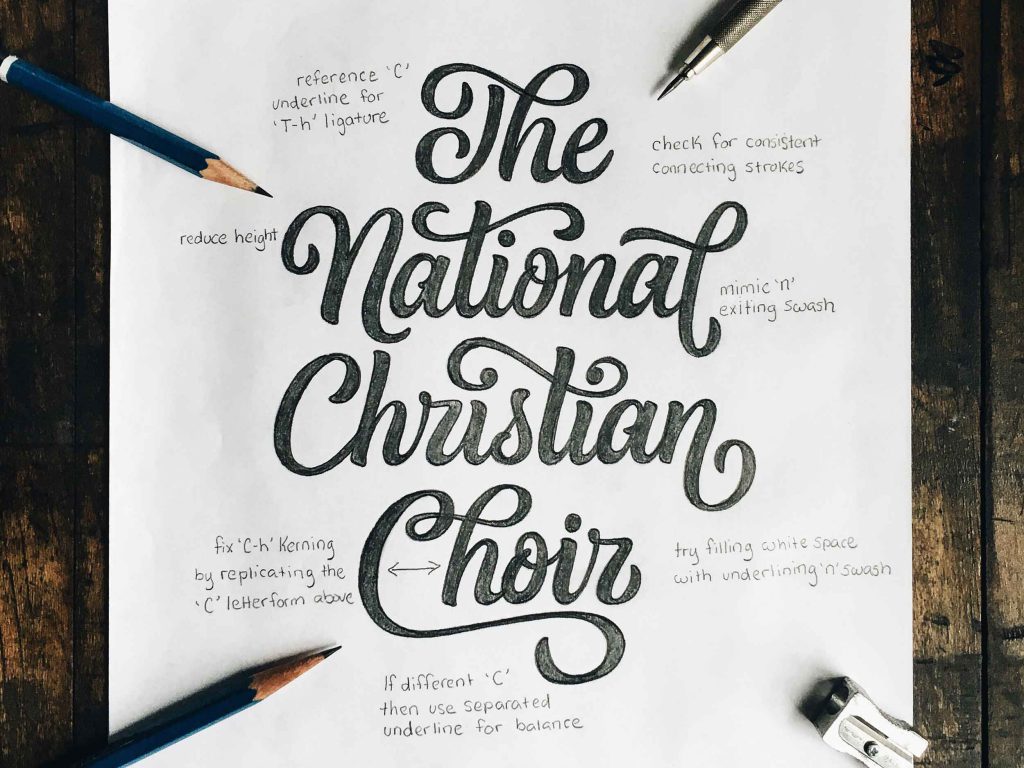

Colin Tierney runs Tierney Studio, a Baltimore-based design studio that specializes in hand lettering, calligraphy and branding. To Colin, details that no one might ever notice are integral to the final design. His favorite part of the process is the initial pen to paper phase when he’s hashing out all of his ideas—the good and the bad.

Colin loves throwing on some headphones and listening to music. Music is a passion of his that isn’t directly related to design, so it’s easy to get away from the work and find another source of inspiration through a different kind of love. He recommends to aspiring calligraphers and hand lettering artists his Crayligraphy series. “I go deep into teaching the fundamentals of calligraphy with a Crayola marker. These lessons are perfect for beginners because Crayolas are cheap, accessible and easier to write with.”

Find Colin on Instagram, Twitter and Dribble.

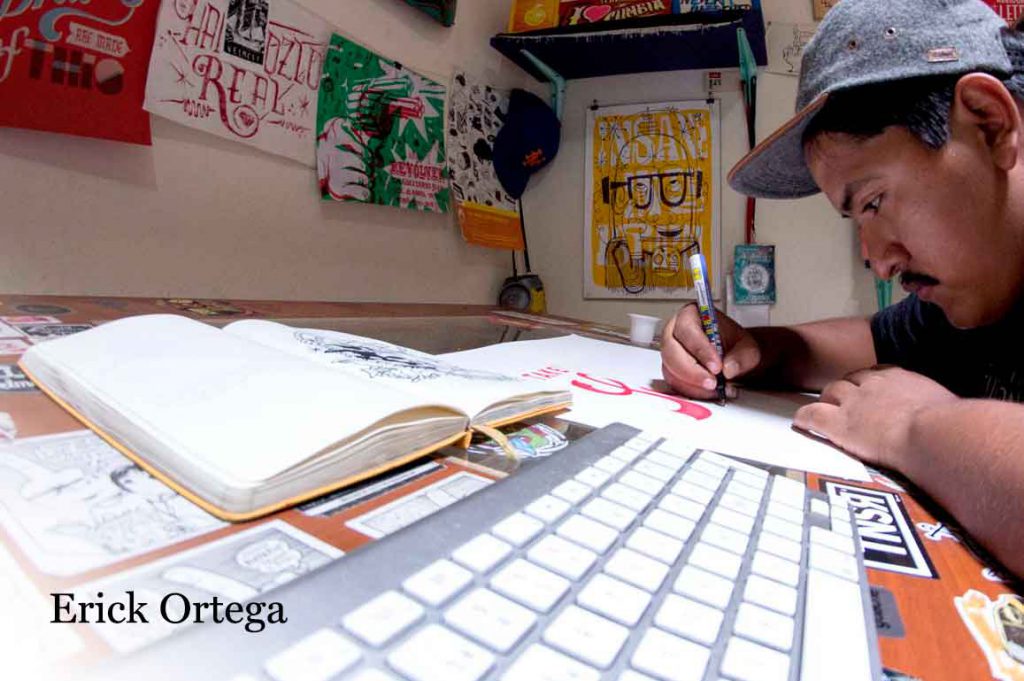

Push Your Craft

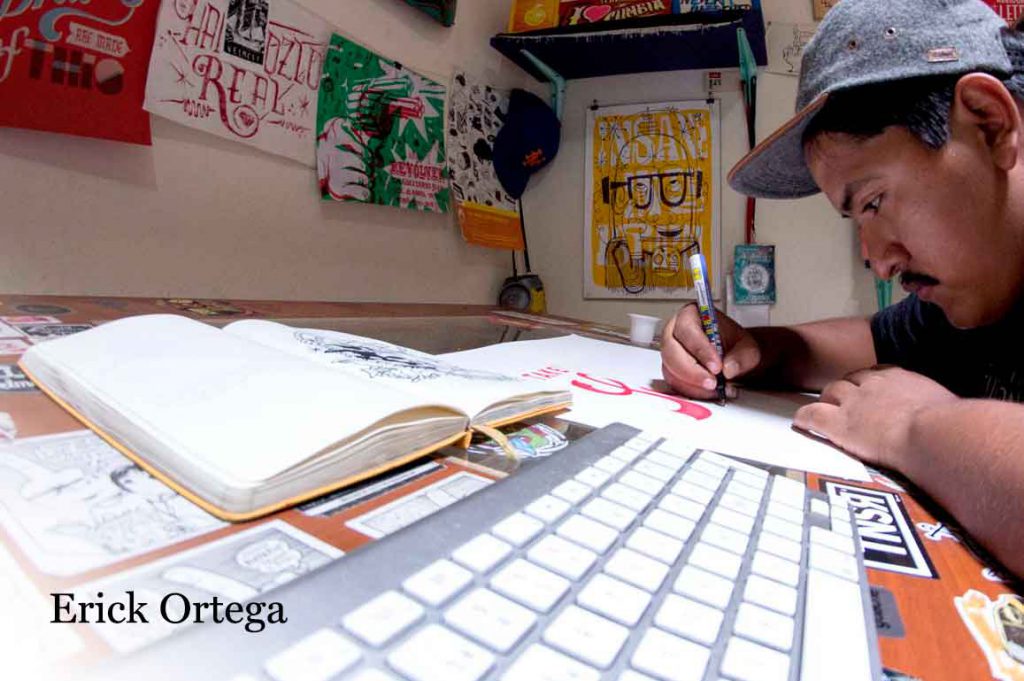

Erick Ortega is a freelance illustrator and lettering artist from Cali, Colombia. The tactile quality of his handmade artwork is one of his trade marks and he enjoys most inking the artwork and finalizing the piece as a digital file. He’s inspired by books, movies, pop culture, but by far, music is his biggest inspiration in many ways. “Being an independent artist is about doing it all yourself and making things happen. Making yourself from scratch and keep pushing your craft to where you want to be next.”

Erick recommends picking up a copy of In Progress by Jessica Hische for both rookies and seasoned designers for information on lettering as a craft, and as a business.

Check out Erick on Behance, Instagram and Twitter.

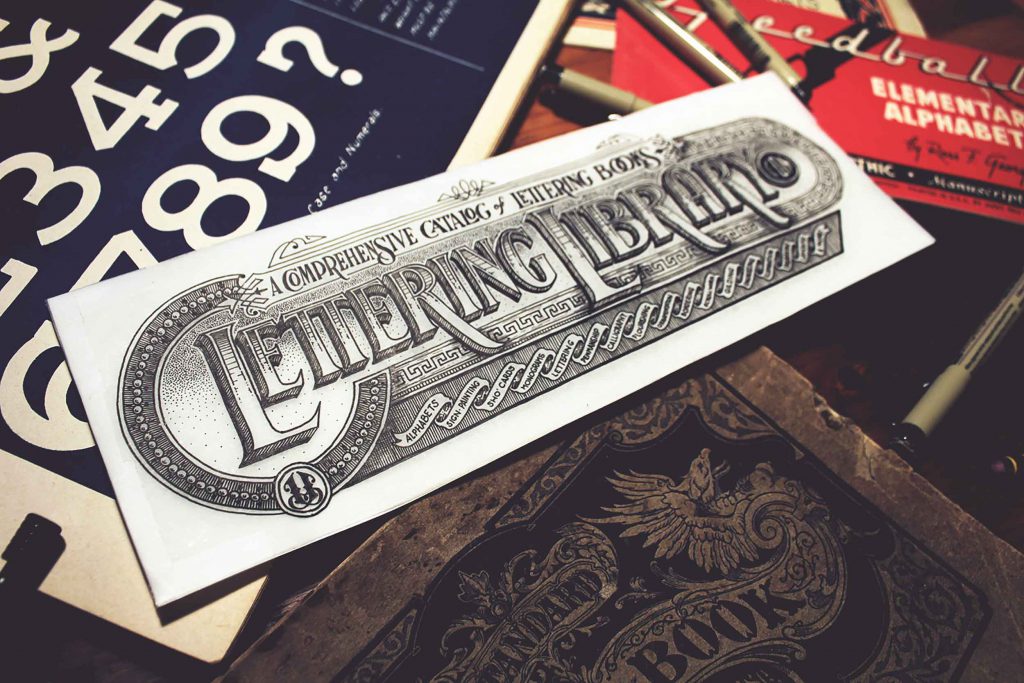

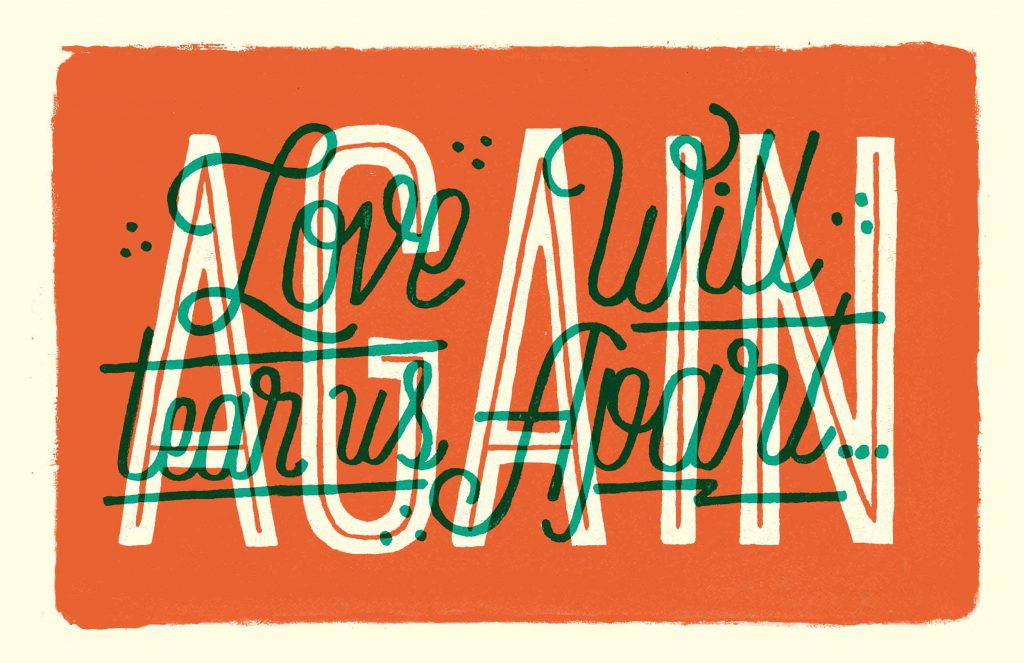

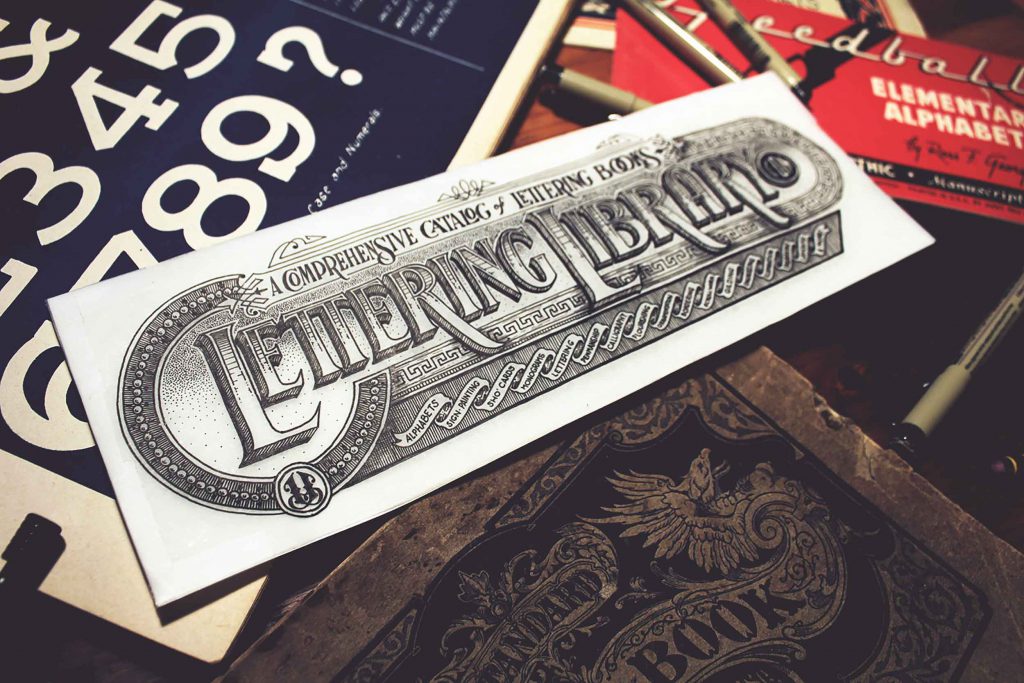

Get the Lettering Bible

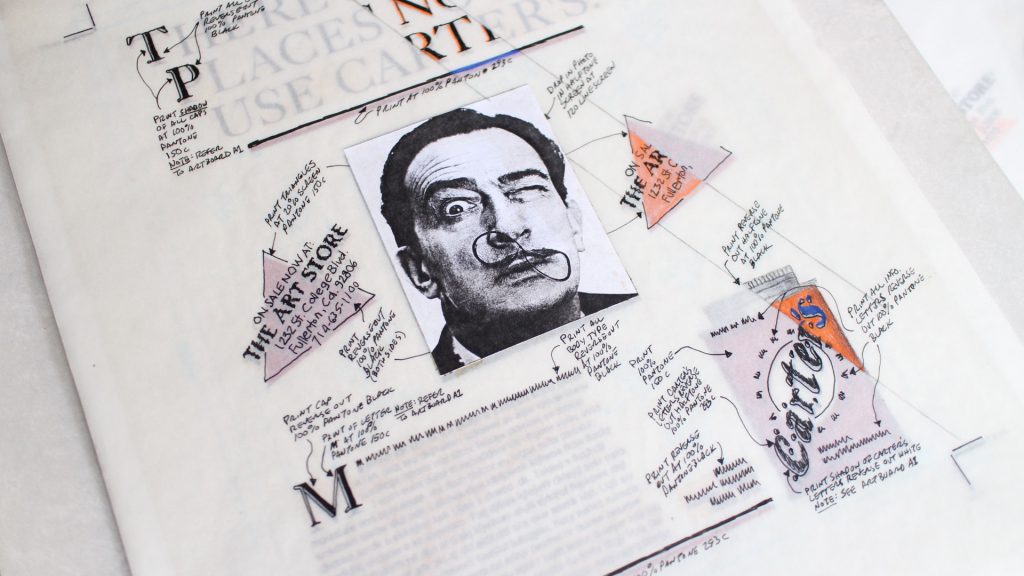

Jason Carne, a freelance graphic designer who letters and designs type in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania, specializes in decorative, ornamental lettering. He is heavily inspired by the past, and constantly looking at old packaging, decades-old photos of signage from decades or centuries ago, and vintage record covers. He admits, “I feel like there was a stronger connection to ones craft in 1916 than there is in 2016, there was a desire to make sure something stood the test of time.”

Jason Carne, a freelance graphic designer who letters and designs type in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania, specializes in decorative, ornamental lettering. He is heavily inspired by the past, and constantly looking at old packaging, decades-old photos of signage from decades or centuries ago, and vintage record covers. He admits, “I feel like there was a stronger connection to ones craft in 1916 than there is in 2016, there was a desire to make sure something stood the test of time.”

-

-

Jason recommends a couple of books for lettering students, the first being Leslie Cabarga’s Logo, Font and Lettering Bible. “Beyond the gorgeous specimens included within its pages, it has tons of insight and secrets from some of the best lettering artists of the past few generations. A close second I’d recommend would be any Speedball book you can find, the most easily attainable being the recently published 100th anniversary edition including original works from Ross F. George (the artists behind the original Speedball books) as well as many modern masters.”

See more of Jason’s work on Dribble, Behance and Instagram.

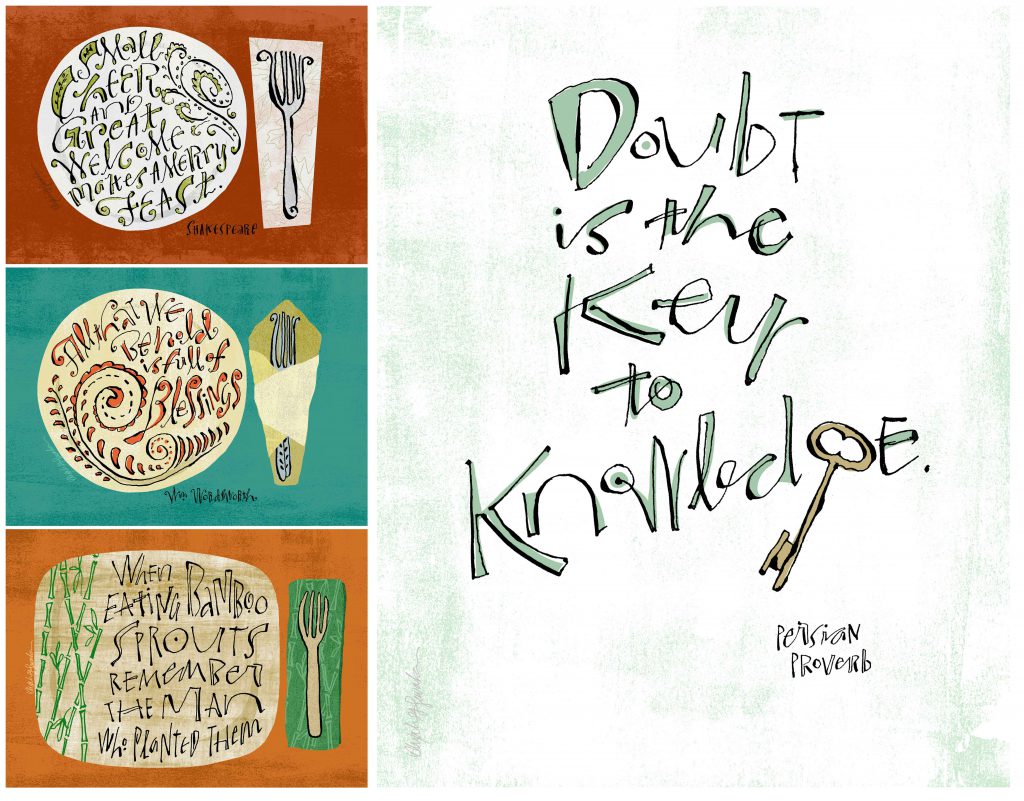

Let the World Inspire You

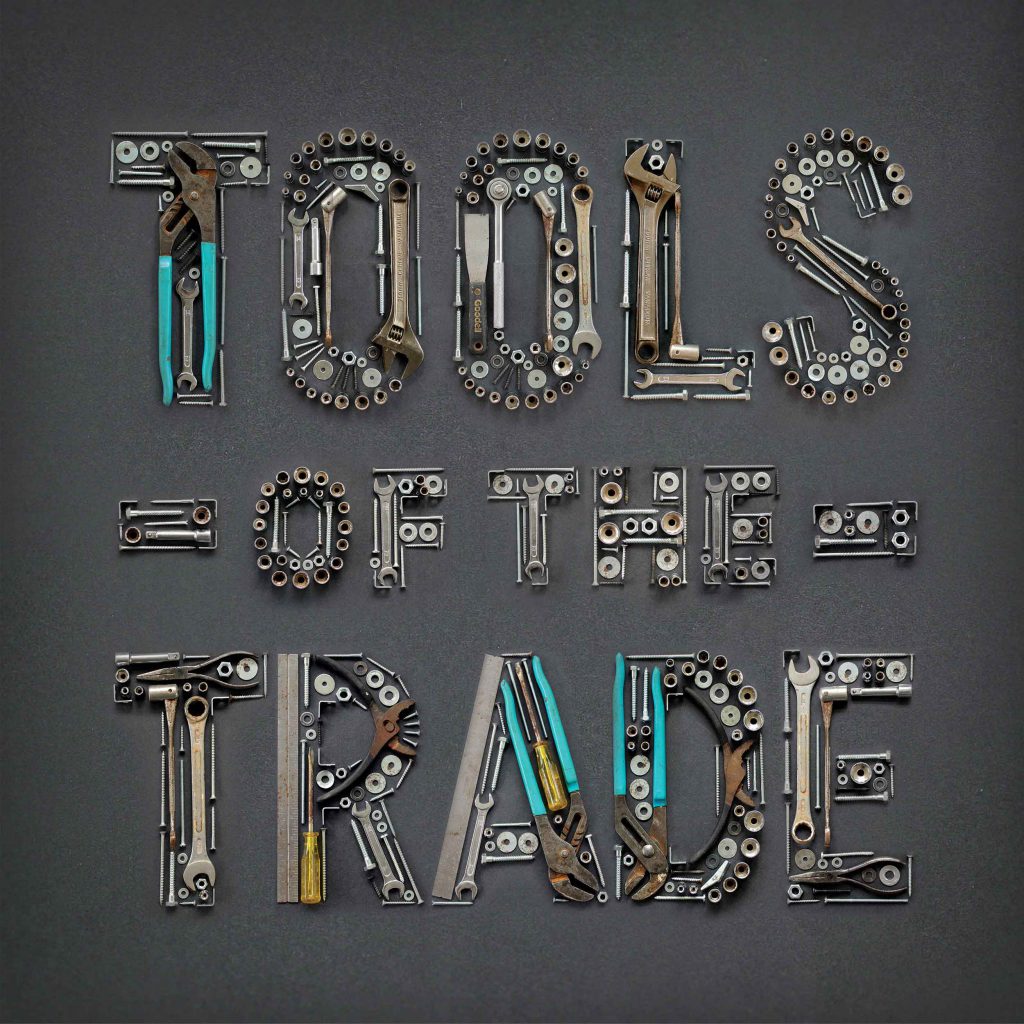

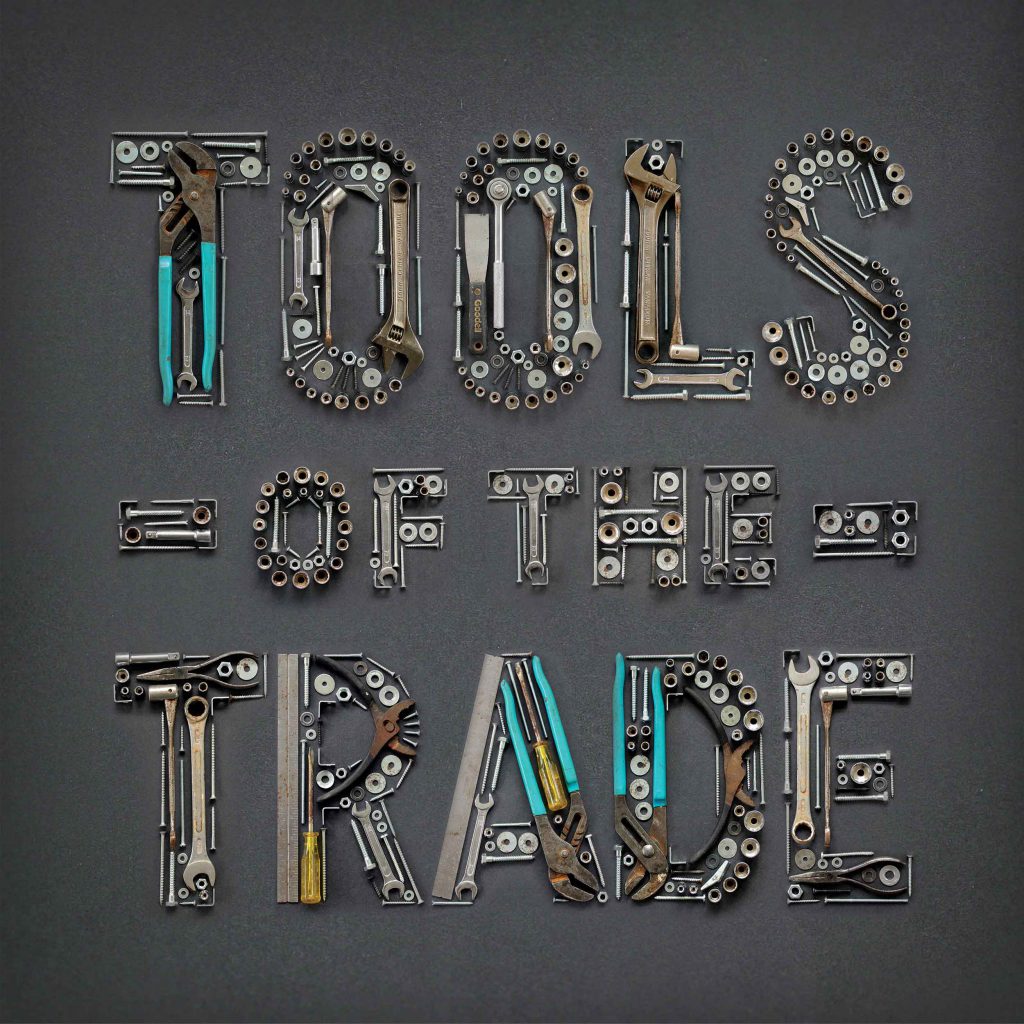

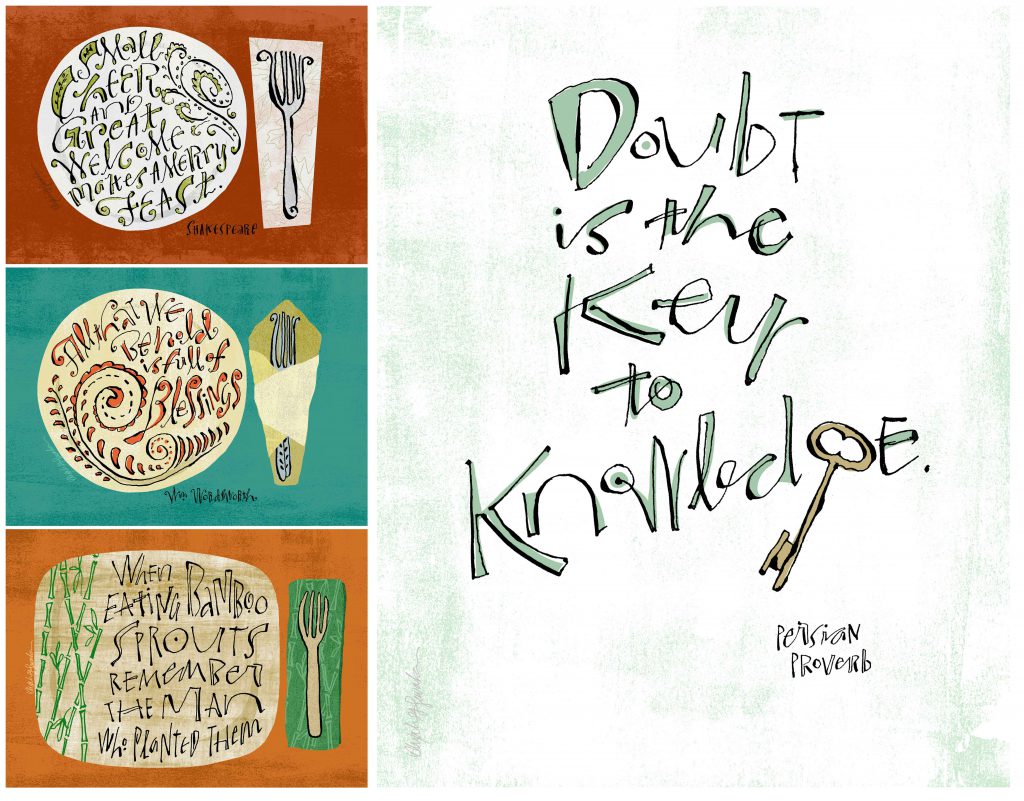

Danielle Evans is an object lettering artist, art director, and animator from Columbus, Ohio. She uses objects and food to create her lettering, and rather than chose mediums for color or trendiness, she crafts the materials and forms around a concept. She loves finding the correct energy in her strokes or stumbling across a new technique as well as the styling process. To get inspired, Danielle’s recommendation would be to go outside.

Danielle Evans is an object lettering artist, art director, and animator from Columbus, Ohio. She uses objects and food to create her lettering, and rather than chose mediums for color or trendiness, she crafts the materials and forms around a concept. She loves finding the correct energy in her strokes or stumbling across a new technique as well as the styling process. To get inspired, Danielle’s recommendation would be to go outside.

-

-

She also attests to one of the most useful books she’s read, which isn’t about lettering at all. “The $100 Startup by Chris Gillebeau was a fantastic reminder that gorgeous letterforms don’t spring from the best reference books, supplies, a fancy studio space, or the most renown peer group,” Danielle remarks. “The book profiles several creatives struggling to actualize their dreams who modestly and resourcefully generate profitable businesses out of small investments. After finishing, I remember realizing my lettering deserved proper investment of my skills, time, and financial backing if it was to flourish.”

Follow Danielle on Twitter, Instagram and her website.

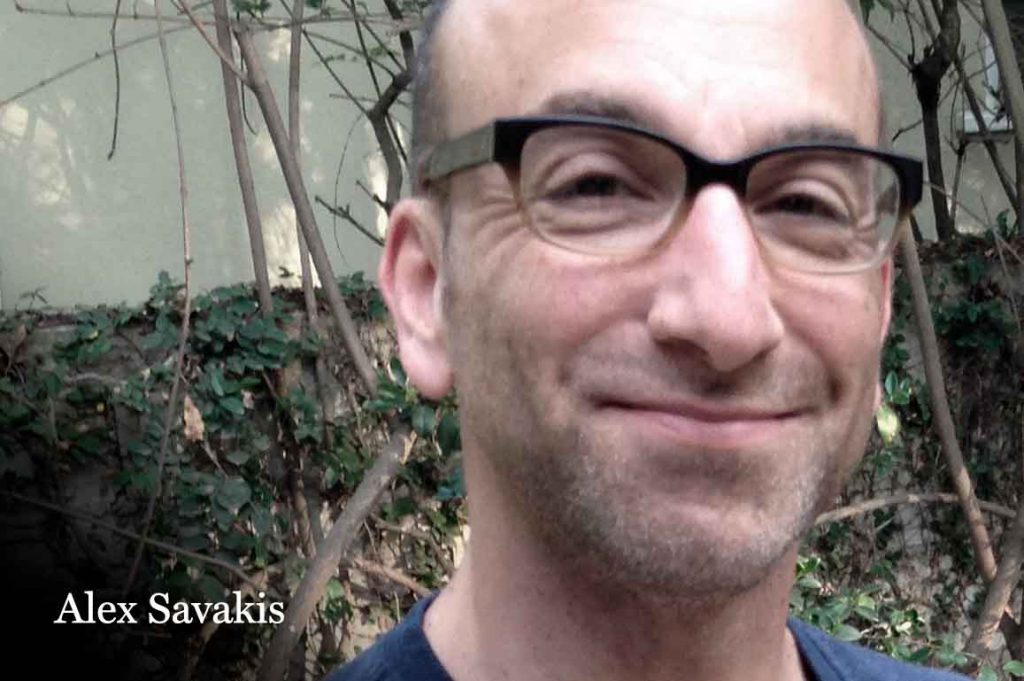

Start on a Letraset Quest

Alex Savakis, a designer and illustrator from Concord, California, deconstructs letters to create new expressions of their forms. He finds the work of fellow lettering artists and calligraphers inspirational, including the American Greetings lettering team with whom he trained with. He says, “Their enthusiasm, spirit and grit inspire me to make something everyday.”

Alex Savakis, a designer and illustrator from Concord, California, deconstructs letters to create new expressions of their forms. He finds the work of fellow lettering artists and calligraphers inspirational, including the American Greetings lettering team with whom he trained with. He says, “Their enthusiasm, spirit and grit inspire me to make something everyday.”

For those learning to letter, Alex recommends finding a Letraset catalog from the 80s. “The catalog was a couple of inches thick, spiral-bound and loaded with typefaces. If a copy is available at a used bookstore, grab it! Also, look online at the lettering work that excites you, deconstruct it to see how it was created, then recreate it in your hand or style. Developing your style will take time, more than you might expect. Keep at it.”

For those learning to letter, Alex recommends finding a Letraset catalog from the 80s. “The catalog was a couple of inches thick, spiral-bound and loaded with typefaces. If a copy is available at a used bookstore, grab it! Also, look online at the lettering work that excites you, deconstruct it to see how it was created, then recreate it in your hand or style. Developing your style will take time, more than you might expect. Keep at it.”

Follow Alex on Instagram, his blog and his website.

Want to find out more about inspiring artists and designer who are leading the way in type and typography? Follow us on Crowdcast. If you’d like to learn more about what we do, visit us at type-ed.com.

Rachel Elnar is a co-founder and producer at TypeEd, where she helps designers implement better typography, efficiently.

This process was great, because you became intimate with the projects because you had your hands on them. You had to know your tools and type really well. Our office was not yet using computer software for design and production, so the task ended up on me to make the transition.

This process was great, because you became intimate with the projects because you had your hands on them. You had to know your tools and type really well. Our office was not yet using computer software for design and production, so the task ended up on me to make the transition. Joseph Alessio is a typographic illustrator based in San Francisco who blends type, letters and animates a host of mixed media in typographic compositions. Joseph’s approach with spatial relationships in type and motion is unique. He loves that part of the process in the middle, when you feel like you can experiment and play and discover – “that’s to me the most exciting and fulfilling part.”

Joseph Alessio is a typographic illustrator based in San Francisco who blends type, letters and animates a host of mixed media in typographic compositions. Joseph’s approach with spatial relationships in type and motion is unique. He loves that part of the process in the middle, when you feel like you can experiment and play and discover – “that’s to me the most exciting and fulfilling part.”

Jason Carne, a freelance graphic designer who letters and designs type in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania, specializes in decorative, ornamental lettering. He is heavily inspired by the past, and constantly looking at old packaging, decades-old photos of signage from decades or centuries ago, and vintage record covers. He admits, “I feel like there was a stronger connection to ones craft in 1916 than there is in 2016, there was a desire to make sure something stood the test of time.”

Jason Carne, a freelance graphic designer who letters and designs type in Saylorsburg, Pennsylvania, specializes in decorative, ornamental lettering. He is heavily inspired by the past, and constantly looking at old packaging, decades-old photos of signage from decades or centuries ago, and vintage record covers. He admits, “I feel like there was a stronger connection to ones craft in 1916 than there is in 2016, there was a desire to make sure something stood the test of time.”

Danielle Evans is an object lettering artist, art director, and animator from Columbus, Ohio. She uses objects and food to create her lettering, and rather than chose mediums for color or trendiness, she crafts the materials and forms around a concept. She loves finding the correct energy in her strokes or stumbling across a new technique as well as the styling process. To get inspired, Danielle’s recommendation would be to go outside.

Danielle Evans is an object lettering artist, art director, and animator from Columbus, Ohio. She uses objects and food to create her lettering, and rather than chose mediums for color or trendiness, she crafts the materials and forms around a concept. She loves finding the correct energy in her strokes or stumbling across a new technique as well as the styling process. To get inspired, Danielle’s recommendation would be to go outside.

Alex Savakis, a designer and illustrator from Concord, California, deconstructs letters to create new expressions of their forms. He finds the work of fellow lettering artists and calligraphers inspirational, including the American Greetings lettering team with whom he trained with. He says, “Their enthusiasm, spirit and grit inspire me to make something everyday.”

Alex Savakis, a designer and illustrator from Concord, California, deconstructs letters to create new expressions of their forms. He finds the work of fellow lettering artists and calligraphers inspirational, including the American Greetings lettering team with whom he trained with. He says, “Their enthusiasm, spirit and grit inspire me to make something everyday.”

For those learning to letter, Alex recommends finding a Letraset catalog from the 80s. “The catalog was a couple of inches thick, spiral-bound and loaded with typefaces. If a copy is available at a used bookstore, grab it! Also, look online at the lettering work that excites you, deconstruct it to see how it was created, then recreate it in your hand or style. Developing your style will take time, more than you might expect. Keep at it.”

For those learning to letter, Alex recommends finding a Letraset catalog from the 80s. “The catalog was a couple of inches thick, spiral-bound and loaded with typefaces. If a copy is available at a used bookstore, grab it! Also, look online at the lettering work that excites you, deconstruct it to see how it was created, then recreate it in your hand or style. Developing your style will take time, more than you might expect. Keep at it.”