Original artwork, Preston Bark

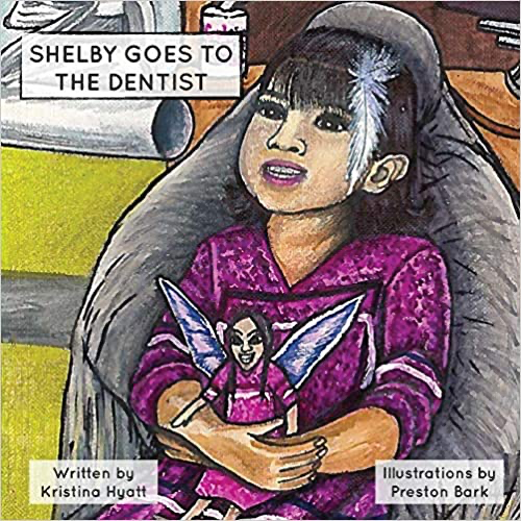

Cherokee culture weaves its way into the work of Preston Bark — from intricate tribal basket designs to mythical symbols like spiders and owls to his choice of color. Wide-ranging topics imbue his work with layered meaning, such as exploring stereotypic labels of Native Americans to shining a light on his native language to the crisis of diabetes in Cherokee communities. His most recent project (that just launched) is a children’s book called Shelby Goes to the Dentist, written by a fellow Eastern Band Cherokee and former Miss Native American USA, Kristina Hyatt, who is also a dental health professional. The underlying idea behind the concept? Representation. The snarled history of the last three hundred years and the indelible impact it has had on Native American cultures is immense — but one piece at a time, Preston is illuminating the world with his impressive work, inviting people to stop and think about a culture that had been submerged but is re-emerging into the light.

Where do you live?

I live in the Wolftown community in Cherokee country, North Carolina. For context, Asheville, the closest town you might know of, is about 45 minutes to an hour away

What kind of work do you make?

I’m pretty versatile. I do wood carving. Stone carving. Pottery. I really want to pursue more painting in the near future. But primarily it’s drawing — anytime, anywhere — I have always turned to drawing.

What drew you to become a creator?

In general, I refer to myself as an artist. It’s something that has always been a part of me — it’s such an integral part of my life. There’s so much emotion attached to my process of creating as far back as I can remember. I believe that it’s a bad idea to leave an idea unfinished. Every idea is like a bridge in the creative process and each unfinished bridge is a barrier to your creativity and its progression.

How does your Cherokee background inform your work?

Outside of the tattoo shop, when I do my personal work, it’s usually tied to the Cherokee culture to some extent. I attach the story or explanation about the piece so the viewer can get an understanding of it. The work I make public has an underlying message of encouraging positivity. I incorporate different elements and designs attached to Cherokee culture — from images, myths, legends, and more.

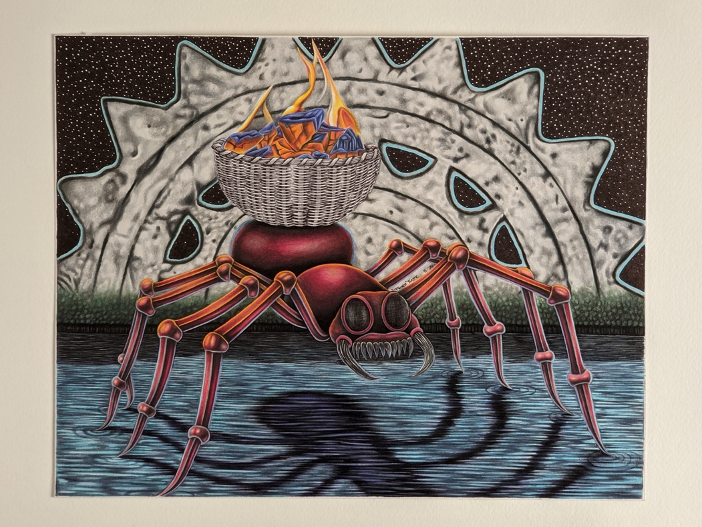

Original artwork, Preston BarkThe spider carrying the flame on its back is based on the Cherokee myth of how and where the “first fire” came about.

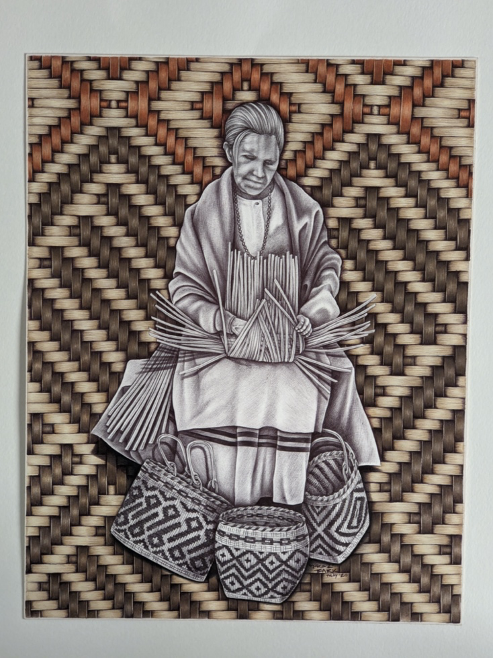

Original artwork, Preston BarkThe “basket maker” shows an elderly Cherokee woman weaving a particular style of Cherokee basketry known as river cane. The design that surrounds her is one of many different Cherokee basket designs, baskets positioned around her feet display different designs.

How did you find your way to doing tattoos?

I actually started when I was 14, and for most of my career, never had a professional mentor until about three years ago, when I was 34. Tattooing is a way for an artist like me to make money. I do a lot of Cherokee-related designs — that’s probably my favorite to do… black and grey Cherokee-related designs.

The majority of people who come for tattoos are from my community. But we have folks who come from out of state to get tattooed by us and get more tourists in the summertime.

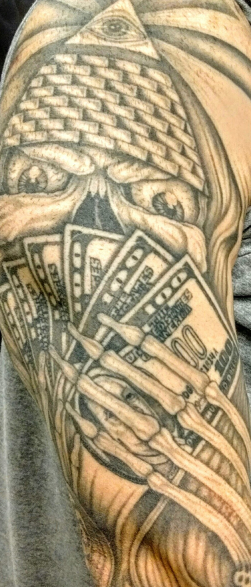

Original artwork, Preston Bark

These tattoos reflect my personal style and how my Cherokee culture influences the tattoos I create. These are examples of black and grey Cherokee designs and portraiture. They touch on topics like the Cherokee language and labels of Native Americans in general.

What has your journey to becoming an artist been like for you?

I spent some time in prison. You can’t understand it until you’ve been there. It inspired me to do better for myself — I know what it’s like to be down and out and hit rock bottom. I know what it’s like to not have your freedom and have your whole life taken from you.

And now that I’m free, I really see the value in the simple things that many other people might take for granted. Seeing the sky. Feeling the ground beneath my feet. The air on my skin. I think that if it was not for my ability to create, I would not be here today. Making art has influenced my journey that much.

Did you find any support inside?

They had all kinds of programs to offer. Most didn’t revolve around art. I was actually asked to teach one of the classes and did so for a little while.

I got out in February 2016 and got back into tattooing about a year later. A family member told me there was an opening in a new shop in Cherokee, but I didn’t have shop experience. I reached out, showed them some of my previous work and tattoos that I had done inside. They gave me a chance. I had always wanted to work in a shop — and I am so thankful that they gave me an opportunity.

When you’re getting out of prison, it’s all about getting that second chance at life.

But when I got out, I was having a really tough time finding a job. I put in so many applications and just couldn’t find work. But then one of the locals here, a female business owner, gave me a chance. And then a few months later, the tattoo shop happened.

Original artwork, Preston BarkThis is a tattoo that I did while incarcerated, it is done with a single needle and the style is known as single needle black and grey.

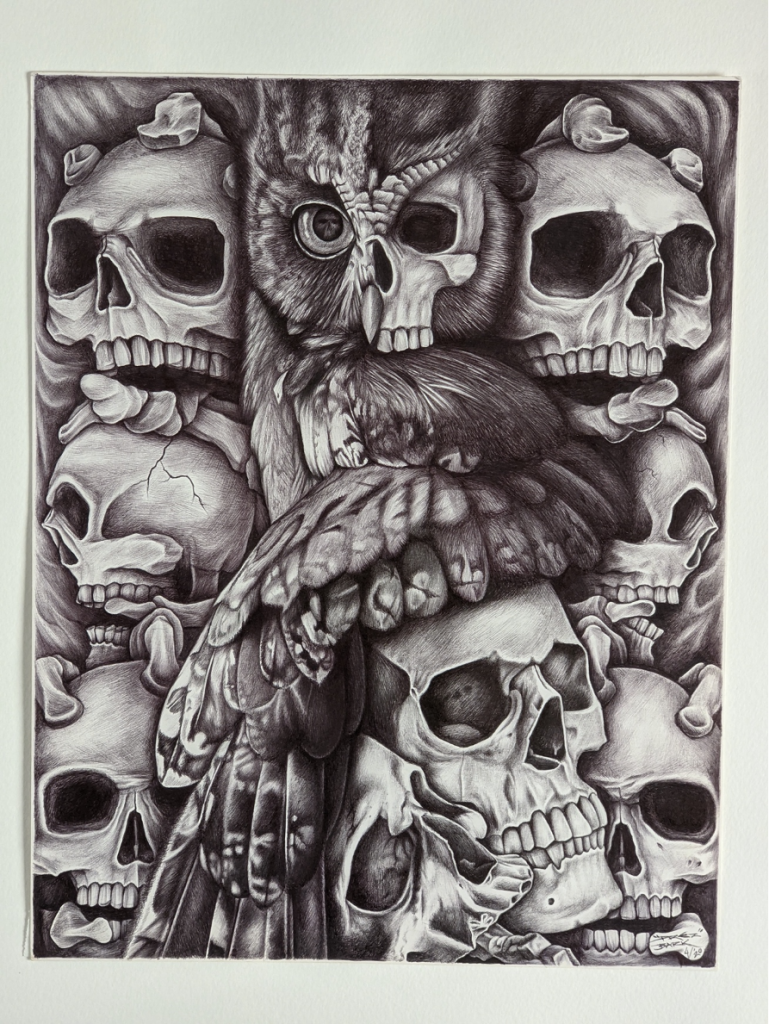

Original artwork, Preston BarkThese is a piece of work I did while incarcerated. It was done with a ballpoint ink pen on handkerchief fabric, which is a common material for drawing “inside.”

Original artwork, Preston Bark

This is another piece that I did while incarcerated, it’s a drawing of my great uncle and my daughter. They’re both deceased, part of what makes this one of my most personal works. I lost my daughter back in February 2007. She was 3 ½ years old and had a lot of medical challenges from the time she was born. If there’s one thing I hold dear to my heart, it is the love I had — and still have — for my daughter, Justice Rain Bark.

What projects are you working on now? What are you excited about now?

I was really looking forward to going back to art school in the next year or so, but COVID has complicated things. I have one more semester left at the Institute of American Indian Arts in Santa Fe, New Mexico.

A lot of people in my community are intimidated about leaving the community, going outside the box — but I just know it’s going to take more to accomplish what I want to accomplish. Cherokee is home and I will always come back to it. But I want to experience more and learn. These are some oil paintings I made in school.

Original artwork, Preston BarkThis is an eagle wand which is used in one of our traditional dances called the Eagle wand or piece pipe dance.

Original artwork, Preston BarkThis is a game ball toss-up in our traditional game of stick ball, which is what lacrosse is based on. The triangular designs in the background are inspired by a traditional Cherokee design called “Road to Soco,” the community in Cherokee where I grew up that’s also known as Wolf Town.

Original artwork, Preston BarkThe owl and skulls drawing speaks to a common Native American belief that owls can be messengers of death or omens of some misfortune in the near future. Growing up, I was taught that if an owl showed up consistently around the home, the death of a loved one was to be expected soon. Owls in Cherokee culture may also be “boogers” or what local Cherokees call “Ski Li” (skilly), meaning booger in Cherokee, and can be an actual person who knows how to shape shift.

You just published a children’s book called Shelby Goes to the Dentist — what is the book about?

In a nutshell: representation. Representation is so important. Native American youth don’t have enough books and resources where the people in them look like them. We wanted to create a book where Native kids would see themselves reflected back. As well, the author’s goal was to help calm folks down who’re nervous about going to the dentist. It’s a book that parent and child can read together before going to an appointment so that the process doesn’t feel so unknown.

What was it like to work on a book?

Kristina gave me the written story for each page and based on what she wrote I would pull inspiration from the words. She had to teach me the dental terminology, she created a primer with pictures which helped me understand the dental health processes. We worked iteratively. Meet. Revise. Finalize. We worked on the project for about a year or two.

While I was creating the art for the book, I tried to keep in mind the audience — children. I wanted to keep it colorful and keep their attention. I wanted the drawings to convey an authentic look at our Cherokee culture in a modern place. If you look at some of the clothing that’s worn, it’s our traditional dress, but wanted to make sure that the art didn’t fall into some classic Native American stereotypical tropes.

How did you and Kristina connect?

I am an established artist here in Cherokee, there’s a lot of talent here. I think she chose me partly due to our cultural connection. But also, I had worked on two children’s books before that didn’t end up getting published. I did both of those while I was incarcerated. I wanted to make sure that this book got published… the third time is the charm!

The journey of many Native American youths is tangled in identity politics and a suppressive history of subjugation — but there is light. The more we make those that have been sidelined central protagonists, the more inclusive and rich our world will be. If you want to learn more about Preston Bark’s work, please visit authenticallycherokee.com, and to view his fine art collection, visit quallaartsandcrafts.com.

About the author.

An award-winning creator and digital health, wellness, and lifestyle content strategist — Karina writes, edits, and produces compelling content across multiple platforms — including articles, video, interactive tools, and documentary film. Her work has been featured on MSN Lifestyle, Apartment Therapy, Goop, Psycom, Pregnancy & Newborn, Eat This Not That, thirdAGE, and Remedy Health Media digital properties.