As copywriters, editors, and creatives, we use language and ideas to persuade, inform, promote. We may communicate across vastly different communities and cultures, with different standards and norms. And our choices have influence. So how do we manage to talk about race, ethnicity, gender, sexual orientation, disability, economic status, and other identities in a fast paced, rapidly changing—and often politically volatile—environment?

I’ll start by sharing that I’m a writer with experience in activism and communications for social justice organizations. I’m not an expert and my lived experience has provided both some privilege and challenges around identity. I’ve made mistakes and I will make others. I’ve encouraged other writers to rethink some of their choices. And I have my own discomfort about writing this piece because it is a contentious topic and messing up can seem risky.

Language Evolves

Words come into our lexicon all the time through cultural exchanges, new technologies, or memes that stick. Perhaps you’re an etymology nerd who knows that words like “ketchup” come from the Chinese or that “thagomizer” (the spikes on the tail of a dinosaur), was used in the Far Side comic before becoming informally adopted by scientists. Maybe you look out for which words get added to the dictionary every year. Or perhaps you readily accepted the use of “they” pronouns or dropping the Oxford comma.

No matter what, you know that we don’t speak Dickensian English. We generally accept that language changes. So why are some people so resistant to change and to feedback about the language and choices that they make? In My Grandmother’s Hands: Racialized Trauma and the Pathway to Mending Our Hearts and Bodies, Resmaa Menakem describes “white-body supremacy.” He writes that the trauma and history of racism is felt within and upon the body by white bodies, by Black or other dark bodies, and by the bodies of public safety professionals. That fear and pain in the body, he argues, is what needs to be settled and metabolized through somatic (body) practices. In other words, people get activated in their primal brains, and their reactions to this discomfort reflect this.

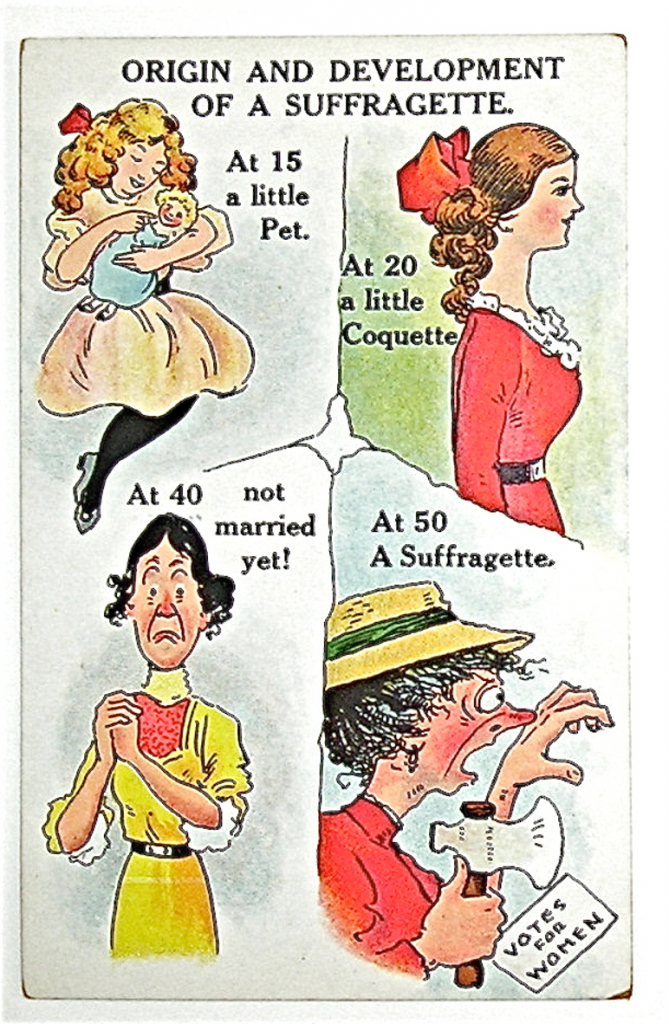

Just as some words enter into the language, other words or phrases get phased out because they have sticky historical connotations or are outright offensive. It might take some education and understanding of history to learn that the phrase “grandfathered in” or the word “boss,” for example, have their roots in our racial history. Many people refrain from using words with negative connotations around mental health or disability. Some women cringe at the idea of being called ma’am, while, regionally and generationally, others may find it polite. Know your audience and interrogate the language that is used.

Be Curious and Ask Questions

Some people bemoan that there isn’t a complete list that they can refer to of words or phrases that are problematic, or that historically have negative or harmful meanings. The path to justice isn’t linear and known. We must accept that there will never be a comprehensive list because language continues to change — and we continue to analyze and learn. Don’t let the fear of making a mistake deter you from engaging with challenging social and political issues. Or assume that because you’ve read a book on the subject, that you have completed the work or that things won’t continue to change.

Be Transparent

Think about the choices that you make and why. Acknowledge them. Ask people you are describing how they want to be identified. For example, some people in the disability community prefer the phrasing “person with a disability” because it is “person first” language; others favor identity first language, such as “disabled person.” Differences could be regional, like the use of “Anglo” in the southwest, or they could be generational, like the use of “queer” versus “gay,” or they could be highly personal. Language that centers violence, like “fight for x,” is also increasingly seen as problematic by some clients.

If You Do Make a Mistake, Apologize and Learn from It

When a listserv that’s geared to media professionals recently sent out an email with a subject line that completely missed the mark and insulted people with disabilities, they certainly heard from other writers. But they promptly understood and accepted that they made a mistake. They sent another email apologizing: no dancing around the issue, simply accepting that an error was made and making a commitment to do better.

That said, there are excellent resources for creatives who want to be aware of the language they employ:

- Sum of Us has a comprehensive resource, A Progressive’s Style Guide.

- Autistic Hoya wrote a thorough blog post about language and ableism. The Center for Disability Rights has its Disability Writing & Journalism Guidelines. Other considerations include How to Write Better Alt Text for Images.

- The Understanding Slavery Initiative explains word choices and language around transatlantic histories and legacies.

As writers, we can easily say something differently or by using different words. Don’t get stuck or attached to using a familiar phrase that is outdated. Shakespeare was so skilled at this, there’s even a Shakespearean insult generator. Find creative solutions to words and phrases that fall out of favor.

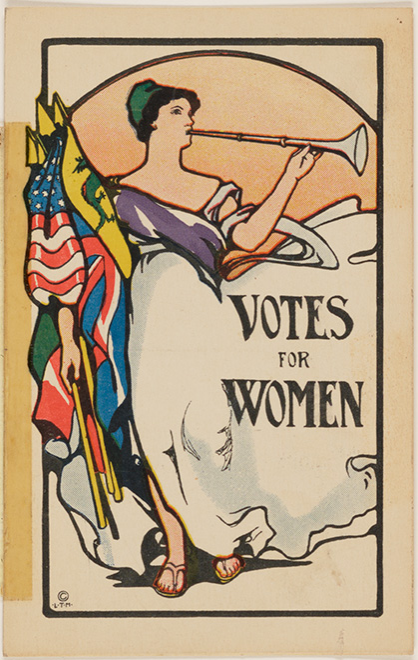

We’ve recently heard from many companies and brands that acknowledge the work they need to do around racial justice. These are good things and barometers of change. Perhaps your company is newly committed to racial justice or maybe it was at the forefront.

It’s critical to listen to feedback and to correct our mistakes. What might be acceptable today might not be acceptable tomorrow. When change is necessary, as writers, we can be stewards of it.

About the author.

Jess Powers writes about marketing, food, and wellness. She has experience in nonprofit communications and emergency management. Follow her @foodandfury.

Image credit:

Image credit:  Image credit:

Image credit: