You might have imagined that at this point, there is more robust diversity in medicine, but the old truth that doctors skew white and male still holds. Only 5 percent of American physicians today are African American — and just 2 percent are Black women. Unpacking this statistic is complex. Part of the problem is pipeline — at American Medical Schools, only 7% of the student body identify as Black. Other components of this grim reality lie in the alleyways of racism, both implicit and explicit. The women of color who do make it through the system to become physicians have to reckon with a medical care landscape that often leaves them, as Black women, vulnerable to more significant injury.

Research shows that implicit racial bias may cause doctors to spend less time with Black patients and that African Americans receive less effective care. Healthcare providers are more likely to underestimate their Black patients’ pain, dismiss their complaints, and ignore their symptoms. The sad truth is that racism disproportionately affects the quality of care that birthing mothers receive.

The birth story of tennis supernova Serena Williams is a stark warning of how the system can fail even the most privileged Black women.

The day after giving birth to her daughter Alexis Olympia Ohanian, Williams felt short of breath and alerted her healthcare providers that she was having trouble breathing. Keenly aware of her body and history of developing blood clots in her lungs, she was particularly concerned. But they ignored her concerns, chalking it up to the medication Williams was on: “it’s making her confused,” they said. But Serena Williams persisted and was eventually able to press her providers to give her the care she needed. It saved her life. For so many Black women, however, when a doctor’s initial reaction is not to take their symptoms or pain seriously, they don’t get the care they need — and often suffer greatly for it. The sad thing is that Serena William’s story is all too common. African American maternal mortality rates are a whopping three to four times higher than for white women — and these deaths are often preventable.

All of this makes the success of Dr. Antonette Whitehead even more notable — she is a doctor, despite being a member of a group for whom medicine is not equal. Being a Black woman who delivers babies is social justice in action. And for her POC patients, she offers the opportunity to lay some thorny fears to rest. But Dr. Antonette Whitehead is not just a bringer of babies — she is a bringer of change. Let’s step inside her world to learn more.

What is your background?

I am part Cherokee and Seminole on my Mom’s side and Choctaw on my Dad’s side. Also, my paternal grandmother is from the Bahamas, so there’s Caribbean too, mixed with African American, of course.

When did you know you wanted to be a doctor?

My desire to be a doctor started at 7. My mom had high blood pressure and high cholesterol, and suffered a pretty significant heart attack early on. She loves to tell a story about me dissecting turkey for Thanksgiving and having an iron stomach. At first, my draw to medicine was heart-focused because I saw my mom in pain — I wanted to heal the heart. But then in college, I took a lot of Women’s Studies courses and began to learn about the health care women were receiving. It was the beginning of my segue to Obstetrics and Gynecology. I did a research project based on women’s experiences with their first and second labors and genuinely enjoyed the research. I kept moving towards the birth part of the human experience. By the time I got to medical school, that’s all I wanted to do — make sure women had good and safe deliveries, solid healthcare, stellar prenatal, and health maintenance.

You mentioned your mother as part of what inspired you to become a doctor, what kind of work did your family do?

If you look at our family history in terms of life callings, it’s all over the place — a lot of teachers. A lot of people who work on the line — I’m from Detroit, aka Motor City. A lot of blue-collar. My sister got her Master’s and Ph.D. in nursing; she researches heart health and women of color.

My uncle is an anesthesiologist. Other than that, no lineage of people who went to medical school, which highlights a prevalent disparity between majority and minority. My dad has a business background; he worked with automotive companies and then went back to school and got a Master’s; he now teaches history. My mother finished high school but never went to college. She jokes that all our degrees are her degrees because she was the bedrock that got us through.

Where did you go to medical school?

I went to Wayne State University in downtown Detroit, about a mile away from where I grew up. I tried my hardest to get to NYC but didn’t land here till I was 30. I did my undergraduate degree at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and moved home after. Wayne State was a great place to go to school. The hospital attached to the school cares for a very inner-city population. The patients didn’t have a lot of resources and were often very sick, but I learned a great deal from them and felt privileged to be able to help. The beautiful thing about my training was that it was so hands-on and intense. By the time I did my residency in Chicago, I felt I had far more experience taking care of very sick and complicated patients than someone coming from a more advantaged medical school climate.

The cool thing about going to medical school in Detroit was that it allowed me to see more people like me, which felt very empowering. Because it is in downtown Detroit, many of the people who go to school there are from Detroit and are African American and Latino. People of color tend to stay there, so my medical school experience was, perhaps, unique.

How did diversity impact your medical school experience?

At Wayne State University, I was part of a diverse student body, being taught by diverse faculty, and treating diverse patients. I loved that and felt like that was very encouraging. In contrast, when I did my residency at Northwestern in Chicago, I was among the first African American residents to be part of their program in 15 years! Hard to believe but true: a peer of mine and I were the first two people of color in 15 years. At Northwestern University, the people I was learning from were mostly majority, not people of color as they had been at Wayne State. It was a definite shift. There were two African American doctors that I tried to model myself after, and some of the majority teachers too, but it was definitely a different experience. But I have to say that I’m so proud of them as a program. We were trailblazers, and since then, Northwestern has kept up diversity in the program!

Did you experience any challenges related to race or gender when you were in residency?

While I don’t think that I encountered attending physicians who were awkward around me or made me uncomfortable, I sometimes sensed that with the patients. “Are you part of building services, are you a nurse, are you housekeeping?”

Has bias impacted you professionally and personally as a doctor in New York?

I’m very patient-focused and patient-centered, it’s part of why I think I get along so well with the team at NYU. I am all about letting women labor and helping them have a safe and awesome birthing experience. But sometimes, I am taking care of a woman during her labor journey and make a recommendation about what we should do next — and they just don’t hear or accept what I’m saying at all. Then someone comes behind me and suggests the very same thing, and they say yes. I wonder if it’s racism? Sexism? Ageism? All three — none? Is it about seniority, or is it because I’m a woman of color? I’m not sure. I can’t figure out which it is. My medical assistants (who like to make good-natured fun of me for spending so much time with patients) say: “I don’t understand why people are not listening to you. They’d listen to this doctor and that doctor.”

What about interfacing with other doctors?

At NYU, there’s one person I can think of that I had to “prove” myself to: an older male doctor in a position of power. I worked with him for almost eight years, and in all that time, he had never complimented me and continually questioned my management and patient care. One day, however, after a particularly tricky Cesarean section, he walked out of the operating room and said to the patient’s family, “Dr. Whitehead did an excellent job today…” You have to really prove yourself to him before you earn his respect — more for some than for others. The realm of Ob/Gyn was once very male-dominated but has changed considerably over the last two decades. He’s older, so I’ve wondered if this was an issue of seniority, but I suspect sexism was at play. I also wonder if it has to do with me being a woman of color.

As a high-achieving BIPOC female Ob/Gyn, do you face obstacles regularly?

I honestly don’t. However, I like to let my patients get to know me, and feel that my hurdle is that I have some fears that there may be judgment around me being queer — so I don’t let everyone into that side of me.

How has the social justice awakening sparked by George Floyd’s death affected you professionally?

The last few months have been a little difficult with unrest around social justice issues, pandemic challenges, people at home. I have been talking to my daughter about racial injustice, and that has carried over to work.

My colleagues and I have been discussing the protests and social justice awakening — and I’ve shared that I want us as a practice to take a stance on what’s happening. I think it has helped open their eyes. I feel they have begun to recognize me more as a woman of color. Until these last few months, I never talked about race. I don’t think that there was un-recognition in a negative way; they simply saw me as their talented, competent medical partner. One nurse that I am close to at NYU said: “Please don’t take this the wrong way, I’ve always thought that you were awesome, but I didn’t even think about the fact that you’re African American until now.” But now, as a queer woman of color, I have become more vocal about wanting to establish our practice as one that cares for ALL women. Happy to say that my colleagues have become a little more woke.

My wife, Candace, jokes that I’m having a re-awakening that I’m a Black woman (laughs). Becoming a mother, raising a woman of color, makes me feel I have to have something more to say about things. The silver lining of this pandemic and social unrest is that people have been part of the change. Now my question is, what am I going to do about that?

What is it that you are drawn to do about social justice?

I have several patients that teach in Harlem and in Brooklyn, who have invited me to come to talk to children in their schools and be a mentor. I started mentoring just before COVID-19 hit. Thinking back to college and even high school, it would have been good to see more women who look like me — or men, people of color in general. I want to show that you can be a person of color and achieve your dreams.

Now that I am a mother, doctor, and wife, I am ready to give back more fully to the community. I would love to do something for women in terms of talking about health, how to take care of our bodies. I am thinking about partnering with Cumbe, a center for diaspora dance and music in Brooklyn.

Can you share your insights into the crisis of African American maternal health in the USA?

I have to tell you from a personal perspective when I was pregnant; I was deathly afraid. Even as a privileged woman — with a good income and insurance, and some of my best colleagues taking care of me — I was still very, very worried about developing blood pressure issues or gestational diabetes or any of the other comorbidities that we know are higher for moms of color. I’ll be transparent: I was terrified I could die because my delivery became complicated.

Is this part of why you feel diversity in medicine matters?

Absolutely. My POC patients are sometimes extremely concerned about making sure I am on call for their deliveries because they are afraid that a majority doctor may not be as attuned to what they need for pain management or in the face of complications. “How can I make sure you’re on call when I’m in labor because I’m scared no one will listen to me about my pain control or how I’m feeling. Am I going to be listened to? Will I be heard?”

The great thing about NYU is that we have not seen that discrepancy in maternal health outcomes — and we want to keep it that way. Our nurses have spearheaded a committee called Black Mothers Matter, a group focused on keeping the level of care high for moms of color (and all mothers) by taking a close look at how we manage care for women who come in with possible warning signs like high blood pressure.

Initially, there was some pushback. When we first started talking about this, some doctors and nurses said: “Everyone matters. All moms matter. Why do we have to have a committee about this?” It’s been interesting to see that over the past several months, there has been more and more interest and understanding of why we feel this committee needs to be present. It’s been a cool thing to watch this awareness bloom. And now, I’m so proud to tell my POC patients about the committee and share NYU’s dedication and success in ensuring the health of Black mothers truly matters.

What advice would you give young Black or POC girls who might be thinking about pursuing medicine?

“You’ll never be able to be a mother and have a career.” That was the messaging from some people in my family. Not from majority people — my own family. Believe in yourself and your ability. We tend to beat ourselves up on our journey as women. It will take time, but you can do it, it’s not unattainable. I think that finding mentorship earlier is helpful; I didn’t have that until I got to medical school.

Be positive. Find a mentor. Grab on their coattails — and just GO. Find someone who looks like you who’s doing it who can help show you the way.

Dr. Antonette Whitehead joined the Downtown Women OB/GYN team in August 2011. Moving her practice from the Midwest, she enjoys delivering gynecologic and obstetric care to the women of New York City. Dr. Whitehead received her BS from the University of Michigan in 2003 and her MD in 2007 from Wayne State University. She completed her residency training in Chicago at Northwestern University’s Prentice Women’s Hospital in 2011. Dr. Whitehead completed her board certification in November 2013.

About the author.

An award-winning creator and digital health, wellness, and lifestyle content strategist — Karina writes, edits, and produces compelling content across multiple platforms — including articles, video, interactive tools, and documentary film. Her work has been featured on MSN Lifestyle, Apartment Therapy, Goop, Psycom, Pregnancy & Newborn, Eat This Not That, thirdAGE, and Remedy Health Media digital properties.

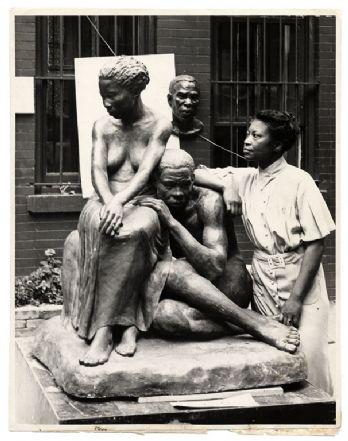

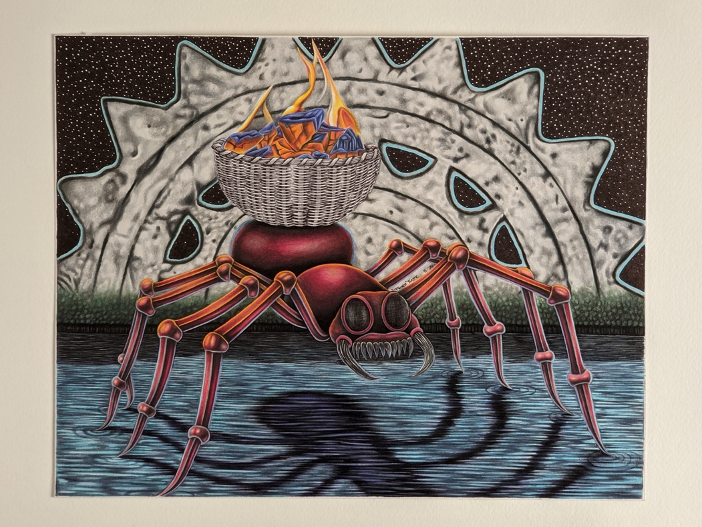

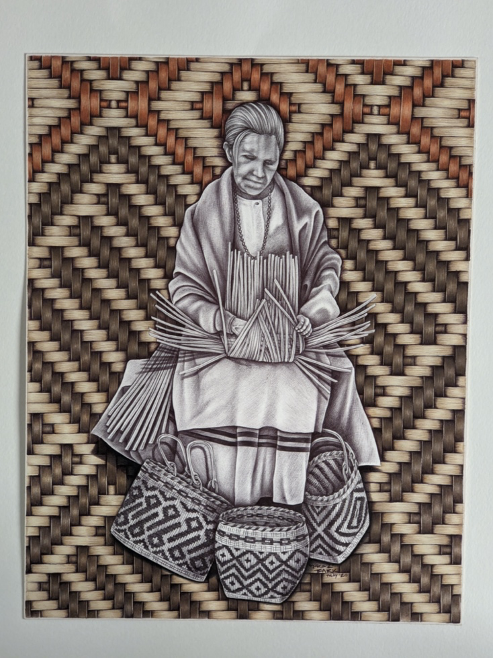

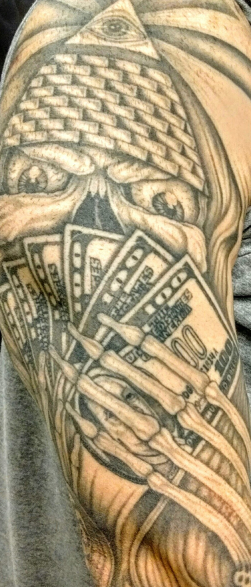

Original artwork, Preston Bark

Original artwork, Preston Bark

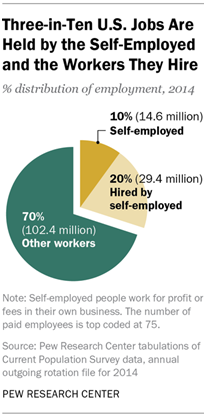

Original artwork, Preston Bark

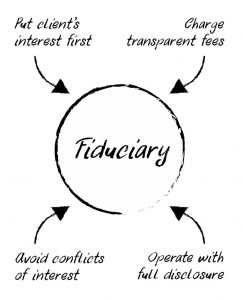

Original artwork, Preston Bark